On India’s 79th Independence Day, we ponder architectural liberty in the context of current practice

As India marks one more year of independence, the issue of freedom in architecture is as pressing today as it was in 1947. At that time of gaining independence, the country was confronted with the immediate task of living, millions had to be rehoused, and no time was available for grand building plans. But from that necessity came a philosophical argument that continues to influence Indian architecture today: the balancing act of embracing global modernity while holding on to local identity.

The newly independent country was presented with a choice that would set the direction of its future architecture: brick or concrete, one that was based on a more profound philosophical dichotomy between old-fashioned craftsmanship supported by Gandhi and the modernism favored by Nehru. Today, almost eight decades on, this conflict takes on a different form in current practice, in which the politics of design function more subtly but no less effectively.

The Freedom to Design with Purpose

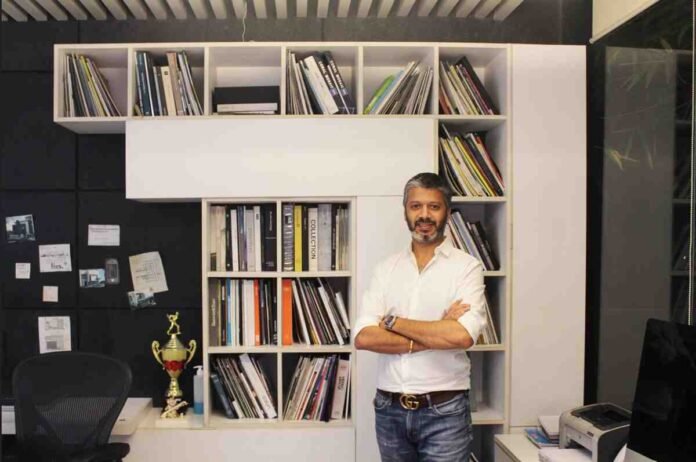

“A building should talk for itself with its idea, and not have philosophical thinking to it.” comments Ar. Sumit Dhawan, Principal Architect of Cityspace’82 Architects. This philosophy indicates maturity in the concept of architectural freedom, not as revolt against tradition, but as the freedom to think and respond genuinely to context and client.

In post-colonial India, architecture became a synthesis that entailed post-colonial re-exploration of origins and balancing both modern technology and native techniques, merging international knowledge with native traditions. This synthesis persists today in practices that eschew the simplistic classification of “traditional” and “modern.”

“I strongly believe in a right balance between form and functionality, embracing a to-and-fro approach,” says Dhawan. “My concept is to engulf the lifestyle and needs of every client, putting myself in their shoes and creating the space as if it were mine.” This thought is a kind of architectural democracy where design is for inhabitants rather than ideology.

The post-independence period saw great interest in reviving traditional forms, but this was coupled with nearly 200 years of British rule and the acceptance of European norms and principles. The challenge wasn’t simply choosing between old and new, but creating architecture that could embody the complexity of a modern nation with ancient roots.

Numerous architects were trained abroad, while others stuck to traditional legacies, resulting in both Modernism and Revivalism, each working towards the identity of the nation. The twin path is what gave birth to today’s pluralistic approach to design.

“Having had nearly two decades of experience, I work and experiment with a variety of design styles, blending one into another.” Dhawan says. This blending is not just about looks, it’s political, embodying the liberty to borrow from the world and yet stay connected to local knowledge.

The idea of freedom of architecture has moved from grand acts of national statement to more subdued acts of genuine reaction. Even in this country with such a wealth of architectural history, current practice has resolutely reached westward for its inspiration, perhaps seeking ‘modernism’. But the most valuable work now comes from a search that is quite different, for relevance, not style.

“I also feel that a building should speak for itself through its idea. ” Dhawan insists. This is not about eschewing influence but about running it through the lens of purpose. The politics at play are understated: in an era of global architectural icons and ‘grammable buildings, deciding to put occupant experience ahead of image is an act of rebellion.

The real political gesture in Indian architecture today may be the refusal to be political at all. Rather than grandly declaring something about national identity or architectural movement, attention is given to what Dhawan describes as “rationalizing both the aesthetics and functional regime of every endeavor.”

This process of rationalization is a kind of architectural democracy. Instead of delivering preconceived solutions, it entails perpetual negotiation between conflicting imperatives: climate and comfort, tradition and innovation, personal desire and common good.

“The intention is to keep coming up with veritable projects and being associated with quality of work within the fraternity and beyond. ” says Dhawan. This humble goal carries within it a radical suggestion, that success for the architect lies not in the accolades of the critics or published notice, but in the lived reality of those who occupy the spaces.

Post-independence architecture is beyond any specific style, largely in harmony with science and contemporary construction methods which are universally acknowledged. Technical freedom thus opened up space for a more subtle handling of cultural expression.

As India celebrates its 79th anniversary of independence, the dilemma isn’t whether to adopt modernity or hold on to tradition, it’s how to use the freedom to choose the right thing at the right time. The politics of design today work in this field of choice, where each choice regarding material, form, and space is an exercise in cultural positioning.

“I test and revolutionize my projects with multiple design styles, blending one into another and creating flawless detailed spectacles. ” Dhawan explains his process. But the spectacle is not the aim, it’s the outcome of more profound immersion in the complicated realities of modern Indian existence.

The most significant political gesture in recent Indian architecture is likely the gentle insistence on relevance rather than rhetoric. Whereas the post-independence generation of architects struggled with issues of national identity through monumental works, practitioners today work at a smaller scale and with different worries.

The politics are no less politic for being subdued. Each decision to subordinate form to function, context to concept, inhabitation to image is a minor act of resistance to the commodification of architecture. Here, political and personal come together in the straightforward act of designing spaces that serve the people who occupy them.

As we celebrate yet another year of freedom, perhaps the most important freedom is the freedom to design on purpose, to make architecture for life rather than ideology, that reflects place rather than trend, that values the lived over the photographed.

In this quiet revolution, each project is a chance to practice the most basic freedom of all: the freedom to care more about how buildings live than how they appear.

This Independence Day reflection is informed by discussions with practitioners who continue to figure out the fraught legacy of Indian architectural freedom, discovering in the workaday practice the room for genuine expression.